Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 16, №3, 2020

Вернуться к номеру

The potential role of benfotiamine in the treatment of diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy

Авторы: V.A. Serhiyenko(1), V.B. Segin(2), L.M. Serhiyenko(1), A.A. Serhiyenko(1)

(1) — Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

(2) — Lviv Regional State Clinical Treatment and Diagnostic Endocrinology Center, Lviv, Ukraine

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

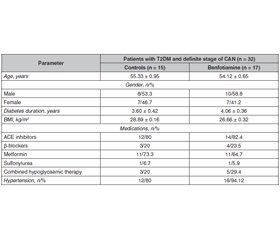

Актуальність. Діабетична автономна нейропатія серця — серйозне ускладнення цукрового діабету, пов’язане з приблизно п’ятиразовим підвищенням ризику серцево-судинної смертності. Автономна нейропатія серця проявляється широким спектром, розпочинаючи від тахікардії спокою і фіксованого серцебиття до розвитку безсимптомного інфаркту міокарда. Значення діабетичної автономної нейропатії серця до кінця не з’ясоване, також не існує єдиного алгоритму лікування. Мета: дослідити вплив бенфотіаміну на стан варіабельності ритму серця, коригований QT, дисперсію QT та просторовий кут QRS-T у хворих на цукровий діабет 2-го типу з автономною нейропатією. Матеріали та методи. Тридцять два пацієнти з цукровим діабетом 2-го типу та функціональною стадією автономної нейропатії серця були розподілені у дві групи лікування: контрольну (n = 15), яка отримувала стандартну цукрознижувальну терапію, та групу 2 (n = 17) — бенфотіамін 300 мг/добу додатково до традиційної терапії протягом трьох місяців. Результати. Встановлено, що призначення бенфотіаміну викликало збільшення відсотка послідовних інтервалів NN, різниця між якими перевищує 50 мс, — pNN50 (Δ% = +45,90 ± 7,91 %, р < 0,05), високочастотної компоненти варіабельності ритму серця під час активного (Δ% = +25,80 ± 5,58 %, p < 0,05) та пасивного періодів доби (Δ% = +21,10 ± 4,17 %, р < 0,05), сприяло зменшенню коригованого інтервалу QT (Δ% = –7,30 ± 1,36 %, p < 0,01), дисперсії QT (Δ% = –27,7 ± 9,0 %, p < 0,01) та просторового кута QRS-T (Δ% = –24,4 ± 10,2 %, p < 0,01). Висновки. Позитивний вплив бенфотіаміну свідчить про доцільність його призначення пацієнтам із цукровим діабетом 2-го типу та функціональною стадією автономної нейропатії серця.

Актуальность. Диабетическая нейропатия сердца — серьезное осложнение сахарного диабета, связанное с примерно пятикратным повышением риска сердечно-сосудистой смертности. Автономная нейропатия сердца проявляется широким спектром, начиная от тахикардии покоя и фиксированного сердцебиения до развития бессимптомного инфаркта миокарда. Значение диабетической автономной нейропатии сердца до конца не выяснено, также не существует единого алгоритма лечения. Цель: исследовать влияние бенфотиамина на состояние вариабельности ритма сердца, корригированный интервал QT, дисперсию QT и пространственный угол QRS-T у больных сахарным диабетом 2-го типа и автономной нейропатией. Материалы и методы. Тридцать два пациента с сахарным диабетом 2-го типа и функциональной стадией автономной нейропатии сердца были распределены в две группы лечения: контрольную (n = 15), получавшую стандартную сахароснижающую терапию, и группу 2 (n = 17) — бенфотиамин 300 мг/сут в дополнение к традиционной терапии в течение трех месяцев. Результаты. Установлено, что назначение бенфотиамина вызывало увеличение процента последовательных интервалов NN, разница между которыми превышает 50 мс, — pNN50 (Δ% = + 45,90 ± 7,91 %, р < 0,05), высокочастотной компоненты вариабельности ритма сердца во время активного (Δ % = + 25,80 ± 5,58 %, p < 0,05) и пассивного периодов суток (Δ% = +21,10 ± 4,17 %, р < 0,05), способствовало уменьшению корригированного интервала QT (Δ% = –7,30 ± 1,36 %, p < 0,01), дисперсии QT (Δ% = –27,7 ± 9,0 %, p < 0,01) и пространственного угла QRS-T (Δ% = –24,4 ± 10,2 %, p < 0,01). Выводы. Положительное влияние бенфотиамина свидетельствует о целесообразности его назначения пациентам с сахарным диабетом 2-го типа и функциональной стадией автономной нейропатии сердца.

Background. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy is a serious complication of diabetes mellitus that is strongly associated with approximately five-fold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy manifests itself in a spectrum of things, ranging from resting tachycardia and fixed heart rate to the development of silent myocardial infarction. The significance of diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy has not been fully appreciated and there is no unified treatment algorithm. The purpose was to investigate the effects of benfotiamine on the heart rate variability, the corrected QT interval, QT dispersion and spatial QRS-T angle in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiac autonomic neuropathy. Materials and methods. Thirty-two patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and definite stage of cardiac autonomic neuropathy were allocated into two treatment groups: control (n = 15) received traditional antihyperglycaemic therapy; group 2 (n = 17) — benfotiamine 300 mg/day for three months in addition to standard treatment. Results. It was found that benfotiamine contributed to an increase in the sum of the squares of differences between adjacent normal-to-normal intervals, pNN50 (Δ% = +45.90 ± 7.91 %, p < 0.05), high-frequency component of heart rate variability during the active (Δ% = +25.80 ± 5.58 %, p < 0.05) and passive periods of the day (Δ% = +21.10 ± 4.17 %, p < 0.05), led to a decrease in the corrected QT interval (Δ% = –7.30 ± 1.36 %, p < 0.01), QT dispersion (Δ% = –27.7 ± 9.0 %, p < 0.01) and spatial QRS-T angle (Δ% = –24.4 ± 10.2 %, p < 0.01). Conclusions. The positive influence of benfotiamine suggests the feasibility of its administration to patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and definite stage of cardiac autonomic neuropathy.

цукровий діабет 2-го типу; автономна нейропатія серця; бенфотіамін; варіабельність ритму серця; коригований інтервал QT; просторовий кут QRS-T

сахарный диабет 2-го типа; автономная нейропатия сердца; бенфотиамин; вариабельность ритма сердца; корригированный интервал QT; пространственный угол QRS-T

type 2 diabetes mellitus; cardiac autonomic neuropathy; benfotiamine; heart rate variability; corrected QT interval; spatial QRS-T angle

Introduction

Materials and methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

- Spallone V., Ziegler D., Freeman R., Bernardi L., Frontoni S., Pop-Busui R., Stevens M. et al. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: clinical impact, assessment, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011. 27(7). 639-53. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1239.

- Serhiyenko V.A., Serhiyenko A.A. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. World J. Diabetes. 2018. 9(1). 1-24. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v9.i1.1.

- Spallone V. Update on the impact, diagnosis and management of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: what is defined, what is new, and what is unmet. Diabetes Metab. J. 2019. 43(1). 3-30. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0259.

- Serhiyenko V.A., Serhiyenko A.A. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy. In: Saldaña J.R., ed. Diabetes Textbook: Clinical Principles, Patient Management and Public Health Issues. Basel: Springer, Cham. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2019, Section 53. 825-850. Online ISBN 978-3-030-11815-0. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-11815-0.

- Vinik A.I., Erbas T., Casellini C.N. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J. Diabetes Investig. 2013. 4(1). 4-18. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12042.

- Vinik A.I., Nevoret M.L., Casellini C., Parson H. Diabetic neuropathy. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2013. 42(4). 747-87. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.06.001.

- Dimitropoulos A., Tahrani A.A., Stevens M.J. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes. 2014. 1(5). 17-39. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i1.17.

- Pop-Busui R., Boulton A.J.M., Feldman E.L., Bril V., Freeman R., Malik R.A., Sosenko J.M. et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017. 40(1). 136-54. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042.

- Serhiyenko V., Serhiyenko A. Diabetic cardiovascular neuropathy. Stavropol: Logos Publishers, 2018. doi: 10.18411/dia012018.49.

- Bernardi L., Spallone V., Stevens M., Hilsted J., Frontoni S., Pop-Busui R., Ziegler D. et al. Toronto Consensus Panel on Diabetic Neuropathy. Methods of investigation for cardiac autonomic dysfunction in human research studies. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011. 27(7). 654-64. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1224.

- Prince C.T., Secrest A.M., Mackey R.H., Arena V.C., Kingsley L.A., Orchard T.J. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, HDL cholesterol, and smoking correlate with arterial stiffness markers determined 18 years later in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33(3). 652-57.

- Desouza C.V., Bolli G.B., Fonseca V. Hypoglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular events. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33(6). 1389-94. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2082.

- Voulgari C., Moyssakis I., Perrea D., Kyriaki D., Katsilambros N., Tentolouris N. The association between the spatial QRS-T angle with cardiac autonomic neuropathy in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2010. 27(12). 1420-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03120.x.

- Voulgari C., Pagoni S., Tesfaye S., Tentolouris N. The spatial QRS-T angle: implications in clinical practice. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2013. 9(3). 197-210. doi: 10.2174/1573403X113099990031.

- Gungor M., Celik M., Yalcinkaya E., Polat A.T., Yuksel U.C., Yildirim E. et al. The value of frontal planar QRS-T angle in patients without angiographically apparent atherosclerosis. Med. Princ. Pract. 2017. 26(2). 125-31. doi: 10.1159/000453267.

- Walsh J.A. 3rd, Soliman E.Z., Ilkhanoff L., Ning H., Liu K., Nazarian S., Lloyd-Jones D.M. Prognostic value of frontal QRS-T angle in patients without clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am. J. Cardiol. 2013. 112(12). 1880-4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.017.

- Raposeiras-Roubin S., Virgos-Lamela A., Bouzas-Cruz N., López-López A., Castiñeira-Busto M., Fernández-Garda R. et al. Usefulness of the QRS-T angle to improve long-term risk stratification of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014. 113(8). 1312-19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.406.

- Deli G., Bosnyak E., Pusch G., Komoly S., Feher G. Diabetic neuropathies: diagnosis and management. Neuroendocrinology. 2013. 98(45). 267-80. doi: 10.1159/000358728.

- Serhiyenko V.A., Serhiyenko A.A. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy: Do we have any treatment perspectives? World J. Diabetes. 2015. 6(2). 245-58. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.245.

- Serhiyenko V.A., Serhiyenko A.A. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy: a review. In: Moore S.J., ed. Omega-3: dietary sources, biochemistry and impact on human health. New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2017. 79-154. ISBN: 978-1-53611-824-7 print. Online ISBN: 978-1-53611-839-1.

- Serhiyenko V., Hotsko M., Snitynska O., Serhiyenko A. Benfotiamine and type 2 diabetes mellitus. MOJ Public Health. 2018. 7(1). 00200. doi: 10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00200.

- Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996. 93(5). 1043-65. PMID: 8598068.

- Adamec J., Adamec R. ECG Holter: guide to electrocardiographic interpretation. New York: Springer-Verlag US, 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78187-71.

- Bazett H.C. An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 1997. 2(2). 177-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.1997.tb00325.x.

- Borleffs C.J., Scherptong R.W., Man S.C., van Welsenes G.H., Bax J.J., van Erven L., Swenne C.A. et al. Predicting ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic heart disease: clinical application of the ECG-derived QRS-T angle. Circ. Arrhyth. Electrophysiol. 2009. 2(5). 548-54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859108.

- Lonsdale D. Dysautonomia, a heuristic approach to a revised model for etiology of disease. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2009. 6(1). 3-10. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem064.

- Berrone E., Beltramo E., Solimine C., Ape A.U., Porta M. Regulation of intracellular glucose and polyol pathway by thiamine and benfotiamine in vascular cells cultured in high glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2006. 281(14). 9307-13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600418200.

- Rašić-Milutinović Z., Gluvić Z., Peruničić-Peković Z., Miličević D., Lačković M., Penčić B. Improvement of heart rate variability with benfothiamine and alpha-lipoic acid in type 2 diabetic patients — pilot study. J. Cardiol. Ther. 2014. 2(1). 1-7. doi: 10.12970/2311-052X.2014.02.01.9.

- Oh S.H., Witek R.P., Bae S.H., Darwiche H., Jung Y., Pi L., Brown A., Petersen B.E. Detection of transketolase in bone marrow-derived insulin-producing cells: benfotiamine enhances insulin synthesis and glucose metabolism. Stem Cells Dev. 2009. 18(1). 37-45. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0255.

- Stirban A., Pop A., Tschoepe D. A randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled trial of 6 weeks benfotiamine treatment on postprandial vascular function and variables of autonomic nerve function in type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2013. 30(10). 1204-08. doi: 10.1111/dme.12240.

- Pácal L., Kuricová K., Kaňková K. Evidence for altered thiamine metabolism in diabetes: is there a potential to oppose gluco- and lipotoxicity by rational supplementation? World J. Diabetes. 2014. 5(3). 288-95. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i3.288.

- González-Ortiz M., Martínez-Abundis E., Robles-Cervantes J.A., Ramírez-Ramírez V., Ramos-Zavala M.G. Effect of thiamine administration on metabolic profile, cytokines and inflammatory markers in drug-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2011. 50(2). 145-9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0123-x.

- Luong K.V., Nguyen L.T. The impact of thiamine treatment in the diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2012. 4(3). 153-60. doi: 10.4021/jocmr890w.

- Katare R.G., Caporali A., Emanueli C., Madeddu P. Benfotiamine improves functional recovery of the infarcted heart via activation of pro-survival G6PD/Akt signaling pathway and modulation of neurohormonal response. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010. 49(4). 625-38. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.014.

- Kempler P. Review: autonomic neuropathy: a marker of cardiovascular risk. Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. 2003. 3(2). 84-90. doi: 10.1177/14746514030030020201.

- Boghdadi M.A., Afify H.E., Sabri N., Makbout K., Elmazar M. Comparative study of vitamin B complex combined with alpha lipoic acid versus vitamin B complex in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017. 7(4). 241.

- Stracke H., Gaus W., Achenbach U., Federlin K., Bretzel R.G. Benfotiamine in diabetic polyneuropathy (BENDIP): results of a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2008. 116(10). 600-5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1065351.

- Pacal L., Tomandl J., Svojanovsky J., Krusova D., Stepankova S., Rehorova J. et al. Role of thiamine status and genetic variability in transketolase and other pentose phosphate cycle enzymes in the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011. 26(4). 1229-36. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq550.

- Moss C.J., Mathews S.T. Thiamin status and supplementation in the management of diabetes mellitus and its vascular comorbidities. Vitam. Min. 2013. 2. 111. doi: 10.4172/vms.1000111.

- Pillai J.N., Madhavan S. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy and QTc Interval in type 2 diabetes. Heart India. 2015. 3(1). 8-11. doi: 10.4103/2321-449X.153279.

- Veglio M., Borra M., Stevens L.K., Fuller J.H., Perin P.C. The relation between QTc interval prolongation and diabetic complications: The EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study Group. Diabetologia. 1999. 42(1). 68-75. doi: 10.1007/s001250051115.

- Valensi P., Johnson N.B., Maison-Blanche P., Extramania F., Motte G., Coumel P. Influence of cardiac autonomic neuropathy on heart rate dependence of ventricular repolarization in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002. 25(5). 918-23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.918.

- Kardys I., Kors J.A., Van der Meer I., Hofman A., Van der Kuip D.A., Witteman J.C. Spatial QRS-T angle predicts cardiac death in a general population. Eur. Heart J. 2003. 24(14). 1357-64. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00203-3.

- Shoeb M., Ramana K.V. Anti-inflammatory effects of benfotiamine are mediated through the regulation of the arachidonic acid pathway in macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012. 52(1). 182-90. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.444.

- Koufopoulos G., Pafili K., Papanas N. Correlation between type 2 diabetes mellitus and ankle-brachial index in a geographically specific Greek population without peripheral arterial disease. Mìžnarodnij endokrinologìčnij žurnal. 2019. 15(7). 9-14. doi: 10.22141/2224-0721.15.7.2019.186053.

- Ziegler D., Schleicher E., Strom A., Knebel B., Fleming T., Nawroth P., Haring H.U. et al. Association of transketolase polymorphisms with measures of polyneuropathy in patients with recently diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Met. Res. Rev. 2016. 33(4). e2811. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2811.

/92.jpg)

/93.jpg)

/94.jpg)