Журнал «Здоровье ребенка» Том 15, №3, 2020

Вернуться к номеру

Протеазы, деградирующие биопленочный матрикс

Авторы: Абатуров А.Е.

ГУ «Днепропетровская медицинская академия МЗ Украины», г. Днепр, Украина

Рубрики: Педиатрия/Неонатология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

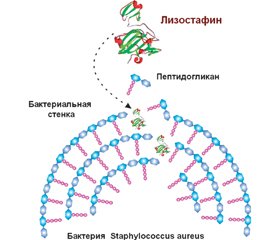

Біоплівки захищають бактерії від діючих антибактеріальних препаратів і застосовують один із механізмів антибіотикорезистентності інфектів. Деструкція матриксу бактеріальної біоплівки призводить до вивільнення бактерій, і вони знову стають уразливими до антибактеріальних засобів. У деградації різних компонентів екстрацелюлярного матриксу біоплівок беруть участь різні ферменти: протеази, глікозидази, дезоксирибонуклеази, що секретуються бактеріями та клітинами макроорганізму. Численні бактеріальні протеази та протеази тваринного походження дозволяють диспергувати біоплівки. Протеази поділяються на дві основні групи: екзо- та ендопептидази. У диспергуванні біоплівки беруть участь екзопептидази. Бактеріальні протеази виконують дві основні функції: по-перше, вони беруть участь у забезпеченні мікроорганізму пептидними поживними речовинами і, по-друге, сприяють розвитку інфекційного процесу. Бактерії кожної родини продукують декілька протеаз, активність яких спрямована проти різних таргетних молекул. Такі бактеріальні протеази, як авреолізин, стафопаїни A і B, стрептококова цистеїнова протеаза, серинова протеаза V8, протеази Spl, лізостафін, протеази Lasb, Lapg, сератіопептидаза, протеїназа К, субтилізин і субтилізин-подібні ферменти, які беруть участь у розщеплюванні матриксу біоплівки, сприяють вивільненню патогенних бактерій, що обумовлює підвищення ефективності антибактеріальної терапії і знижує ризик несприятливого перебігу тяжких бактеріальних інфекцій. Сьогодні показано, що застосування рекомбінантних форм лізостафіну, сератіопептидази, протеїнази К супроводжується зниженням маси біоплівки або повною її деградацією та сприяє саногенезу інфекційних захворювань. Незважаючи на те, що більшість ідентифікованих протеаз з антибіоплівковою активністю сьогодні перебувають у фазі експериментального дослідження, не залишається сумнівів, що лікарські засоби, розроблені на їх основі, стануть препаратами, що будуть використовуватися при лікуванні захворювань, викликаних антибіотикорезистентними інфектами.

Биопленки защищают бактерии от действия антибактериальных препаратов и являются одним из механизмов антибиотикорезистентности инфектов. Деструкция матрикса бактериальной биопленки приводит к высвобождению бактерий, и они вновь становятся уязвимыми для антибактериальных средств. В деградации различных компонентов экстрацеллюлярного матрикса биопленок участвуют различные ферменты: протеазы, гликозидазы, дезоксирибонуклеазы, которые секретируются бактериями и клетками макроорганизма. Многочисленные бактериальные протеазы и протеазы животного происхождения способствуют диспергированию биопленки. Протеазы делятся на две основные группы: экзо- и эндопептидазы. В диспергировании биопленки участвуют экзопептидазы. Бактериальные протеазы выполняют две основные функции: во-первых, они участвуют в обеспечении микроорганизма пептидными питательными веществами и, во-вторых, способствуют развитию инфекционного процесса. Бактерии каждого семейства продуцируют несколько протеаз, активность которых направлена против различных таргетных молекул. Такие бактериальные протеазы, как ауреолизин, стафопаины A и B, стрептококковая цистеиновая протеаза, сериновая протеаза V8, протеазы Spl, лизостафин, протеазы Lasb, Lapg, серратиопептидаза, протеиназа К, субтилизин и субтилизин-подобные ферменты, которые участвуют в расщеплении матрикса биопленок, способствуют высвобождению патогенных бактерий, что обусловливает повышение эффективности антибактериальной терапии и снижает риск неблагоприятного течения тяжелых бактериальных инфекций. В настоящее время показано, что применение рекомбинантных форм лизостафина, серратиопептидазы, протеиназы К сопровождается снижением массы биопленки или полной ее деградацией и способствует саногенезу инфекционных болезней. Несмотря на то, что большинство идентифицированных протеаз с антибиопленочной активностью в настоящее время находятся в фазе экспериментального изучения, не остается сомнений, что лекарственные средства, разработанные на их основе, станут препаратами, которые будут использоваться при лечении заболеваний, вызванных антибиотикорезистентными инфектами.

Biofilms protect bacteria from the action of antibacterial drugs and are one of the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance of infections. Destruction of the bacterial biofilm matrix leads to the release of bacteria and they again become vulnerable to antibacterial agents. Various enzymes are involved in the degradation of various components of the excellular matrix of biofilms: proteases, glycosidases, deoxyribonucleases, which are secreted by bacteria and macroorganism cells. Numerous bacterial proteases and proteases of animal origin contribute to the dispersion of biofilms. Proteases are divided into two main groups: exo- and endopeptidases. Exopeptidases are involved in the dispersion of biofilms. Bacterial proteases perform two main functions: firstly, they are involved in providing the microorganism with peptide nutrients and, secondly, they contribute to the development of the infectious process. Bacteria of each family produce several proteases, the activity of which is directed against various targeted molecules. Bacterial proteases such as aureolysin, staphopaines A and B, streptococcal cysteine protease, V8 serine protease, Spl protease, lysostaphin, LasВ protease, LapG protease, serratiopeptidase, proteinase K, subtilisin and subtilisin-like enzymes that are involved in the breakdown of the bioprotein matrix contribute to the release of pathogenic bacteria, which leads to an increase in the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy and reduces the risk of an adverse course of severe bacterial infections. It has now been shown that the use of recombinant forms of lysostaphin, serratiopeptidase, proteinase K is accompanied by a decrease in the weight of the biofilm or its complete degradation and contributes to the sanogenesis of infectious diseases. Despite the fact that most of the identified proteases with antibiotic activity are currently in the phase of experimental study, there is no doubt that drugs developed on their basis will become drugs that will be used in the treatment of diseases caused by antibiotic-resistant infections.

бактеріальні біоплівки; диспергування; позаклітинні бактеріальні протеази

бактериальные биопленки; диспергирование; внеклеточные бактериальные протеазы

bacterial biofilms; dispersion; extracellular bacterial proteases

Введение

Протеазы, участвующие в диспергировании бактериальной биопленки

Основные бактериальные протеазы

Другие экстрацеллюлярные протеазы

Заключение

1. Abtahi H., Farhangnia L., Ghaznavi-Rad E. In Vitro and in Vivo Antistaphylococcal Activity Determination of the New Recombinant Lysostaphin Protein. Jundishapur. J. Microbiol. 2016 Mar 2. 9(3). e28489. doi: 10.5812/jjm.28489.

2. Adekoya O.A., Sylte I. The thermolysin family (M4) of enzymes: therapeutic and biotechnological potential. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2009 Jan. 73(1). 7-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00757.x.

3. Augustin M., Ali-Vehmas T., Atroshi F. Assessment of enzymatic cleaning agents and disinfectants against bacterial biofilms. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2004 Feb 18. 7(1). 55-64. PMID: 15144735.

4. Bastos M.D., Coutinho B.G., Coelho M.L. Lysostaphin: A Staphylococcal Bacteriolysin with Potential Clinical Applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2010 Apr 19. 3(4). 1139-1161. doi: 10.3390/ph3041139.

5. Berscheid A., François P., Strittmatter A. et al. Generation of a vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) strain by two amino acid exchanges in VraS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014 Dec. 69(12). 3190-8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku297.

6. Blackledge M.S., Worthington R.J., Melander C. Biologically inspired strategies for combating bacterial biofilms. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013 Oct. 13(5). 699-706. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.07.004.

7. Boksha I.S., Lavrova N.V., Grishin A.V. et al. Staphylococcus simulans Recombinant Lysostaphin: Production, Purification, and Determination of Antistaphylococcal Activity. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2016 May. 81(5). 502-10. doi: 10.1134/S0006297916050072.

8. Carlin Fagundes P., Miceli de Farias F., Cabral da Silva Santos O., Souza da Paz J.A., Ceotto-Vigoder H. et al. Nisin and lysostaphin activity against preformed biofilm of Staphylococcus aureus involved in bovine mastitis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016 Jul. 121(1). 101-14. doi: 10.1111/jam.13136.

9. Cherny K.E., Sauer K. Untethering and degradation of the polysaccharide matrix are essential steps in the dispersion response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2019 Nov 11. pii: JB.00575-19. doi: 10.1128/JB.00575-19.

10. Coughlan L.M., Cotter P.D., Hill C., Alvarez-Ordóñez A. New Weapons to Fight Old Enemies: Novel Strategies for the (Bio)control of Bacterial Biofilms in the Food Industry. Front. Microbiol. 2016 Oct 18. 7. 1641. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01641.

11. Dubin G. Extracellular proteases of Staphylococcus spp. Biol. Chem. 2002 Jul-Aug. 383(7–8). 1075-86. DOI: 10.1515/BC.2002.116.

12. Duman Z.E., Ünlü A., Çakar M.M., Ünal H., Binay B. Enhanced production of recombinant Staphylococcus simulans lysostaphin using medium engineering. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019. 49(5). 521-528. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1599393.

13. Figueiredo J., Sousa Silva M., Figueiredo A. Subtilisin-like proteases in plant defence: the past, the present and beyond. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018 Apr. 19(4). 1017-1028. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12567.

14. Fleming D., Rumbaugh K.P. Approaches to Dispersing Medical Biofilms. Microorganisms. 2017 Apr 1. 5(2). pii: E15. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5020015.

15. Gupte V., Luthra U. Analytical techniques for serratiopeptidase: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2017 Aug. 7(4). 203-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2017.03.005.

16. Hogan S., Zapotoczna M., Stevens N.T. et al. Potential use of targeted enzymatic agents in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-related infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017 Feb 16. pii: S0195-6701(17)30102-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.008.

17. Kaplan J.B. Biofilm matrix-degrading enzymes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014. 1147. 203-13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0467-9_14.

18. Kokai-Kun J.F., Chanturiya T., Mond J.J. Lysostaphin eradicates established Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in jugular vein catheterized mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009 Jul. 64(1). 94-100. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp145.

19. Kumar J.K. Lysostaphin: an antistaphylococcal agent. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008 Sep. 80(4). 555-61. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1579-y.

20. Kumar Shukla S., Rao T.S. Dispersal of Bap-mediated Staphylococcus aureus biofilm by proteinase K. J. Antibiot (Tokyo). 2013 Feb. 66(2). 55-60. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.98.

21. Loughran A.J., Atwood D.N., Anthony A.C. et al. Impact of individual extracellular proteases on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation in diverse clinical isolates and their isogenic sarA mutants. Microbiologyopen. 2014 Dec. 3(6). 897-909. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.214.

22. Martínez-García S., Rodríguez-Martínez S., Cancino-Diaz M.E., Cancino-Diaz J.C. Extracellular proteases of Staphylococcus epidermidis: roles as virulence factors and their participation in biofilm. APMIS. 2018 Mar. 126(3). 177-185. doi: 10.1111/apm.12805.

23. Maunders E., Welch M. Matrix exopolysaccharides; the sticky side of biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017 Jul 6. 364(13). doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx120.

24. Mitkowski P., Jagielska E., Nowak E. et al. Structural bases of peptidoglycan recognition by lysostaphin SH3b domain. Sci Rep. 2019 Apr 12. 9(1). 5965. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42435-z.

25. Mitrofanova O., Mardanova A., Evtugyn V., Bogomolnaya L., Sharipova M. Effects of Bacillus Serine Proteases on the Bacterial Biofilms. Biomed. Res Int. 2017. 2017. 8525912. doi: 10.1155/2017/8525912.

26. Mootz J.M., Malone C.L., Shaw L.N., Horswill A.R. Staphopains modulate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm integrity. Infect. Immun. 2013 Sep. 81(9). 3227-38. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00377-13.

27. Nandan A., Nampoothiri K.M. Molecular advances in microbial aminopeptidases. Bioresour. Technol. 2017 Dec. 245(Pt B). 1757-1765. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.103.

28. Nirale N.M., Menon M.D. Topical formulations of serratiopeptidase: development and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Indian. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010 Jan. 72(1). 65-71. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.62246.

29. Oloketuyi S.F., Khan F. Inhibition strategies of Listeria monocytogenes biofilms-current knowledge and future outlooks. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2017 Sep. 57(9). 728-743. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201700071.

30. Oscarsson J., Tegmark-Wisell K., Arvidson S. Coordinated and differential control of aureolysin (aur) and serine protease (sspA) transcription in Staphylococcus aureus by sarA, rot and agr (RNAIII). Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006 Oct. 296(6). 365-80. PMID: 16782403.

31. Otto M. Staphylococcal Biofilms. Microbiol Spectr. 2018 Aug. 6(4). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0023-2018.

32. Park J.H., Lee J.H., Cho M.H., Herzberg M., Lee J. Acceleration of protease effect on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm dispersal. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012 Oct. 335(1). 31-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02635.x.

33. Pietrocola G., Nobile G., Rindi S., Speziale P. Staphylococcus aureus Manipulates Innate Immunity through Own and Host-Expressed Proteases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017 May 5. 7. 166. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00166.

34. Roy R., Tiwari M., Donelli G., Tiwari V. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence. 2018 Jan 1. 9(1). 522-554. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1313372.

35. Rybtke M., Berthelsen J., Yang L., Høiby N., Givskov M., Tolker-Nielsen T. The LapG protein plays a role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by controlling the presence of the CdrA adhesin on the cell surface. Microbiologyopen. 2015 Dec. 4(6). 917-30. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.301.

36. Selan L., Papa R., Tilotta M. et al. Serratiopeptidase: a well-known metalloprotease with a new non-proteolytic activity against S. aureus biofilm. BMC Microbiol. 2015 Oct 9. 15. 207. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0548-8.

37. Shukla S.K., Rao T.S. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm removal by targeting biofilm-associated extracellular proteins. Indian J. Med. Res. 2017 Jul. 146(Suppl.). S1-S8. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_410_15.

38. Silva C.J., Vázquez-Fernández E., Onisko B., Requena J.R. Proteinase K and the structure of PrPSc: The good, the bad and the ugly. Virus Res. 2015 Sep 2. 207. 120-6. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.03.008.

39. Tam K., Torres V.J. Staphylococcus aureus Secreted Toxins and Extracellular Enzymes. Microbiol Spectr. 2019 Mar. 7(2). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0039-2018.

40. Thallinger B., Prasetyo E.N., Nyanhongo G.S., Guebitz G.M. Antimicrobial enzymes: an emerging strategy to fight microbes and microbial biofilms. Biotechnol. J. 2013 Jan. 8(1). 97-109. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200313.

41. Tossavainen H., Raulinaitis V., Kauppinen L. et al. Structural and Functional Insights Into Lysostaphin-Substrate Interaction. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018 Jul 3. 5. 60. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00060.

42. Xu D., Jia R., Li Y., Gu T. Advances in the treatment of problematic industrial biofilms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017 May. 33(5). 97. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2203-4.

/53.jpg)

/54.jpg)

/55.jpg)

/56.jpg)