Резюме

Актуальність. Ультразвукове дослідження є найбільш поширеним методом візуалізації, що використовується для діагностики стеатозу печінки. Метою нашої роботи є порівняння можливостей діагностики стеатозу й фіброзу печінки за допомогою стандартного ультразвукового дослідження, зсувнохвильової еластографії зі стеатометрією та транзієнтною еластографією з визначенням САР. Матеріали та методи. В обстеження включено 90 пацієнтів віком від 5 до 17 років, середній вік пацієнтів становив (12,08 ± 2,71) року. Визначення наявності й ступеня стеатозу печінки проводилось за допомогою апарата FibroScan 502 Touch F60156 (Echosens, Франція) з дослідженням САР. Усім дітям проводилось ультразвукове дослідження паренхіми печінки В-методом з одночасною зсувнохвильовою еластографією й стеатометрією на апараті Ultima PA («Радмір», Харків). Залежно від наявності стеатозу, що визначався за показником САР, й надмірної ваги й ожиріння пацієнти були розподілені на 3 групи: 1 групу становили 45 пацієнтів зі стеатозом печінки й надмірною вагою та ожирінням (50,0 %), 2 групу — 35 пацієнтів із надмірною вагою та ожирінням без стеатозу (38,9 %), 3 групу (група контролю) — 10 пацієнтів із нормальною вагою без стеатозу (11,1 %). Результати. Для хворих зі стеатозом було характерним підвищення ехогенності печінки (75,0 % пацієнтів). У дітей 1 групи в 2,2 раза частіше спостерігалась змінена структура паренхіми печінки порівняно з показниками дітей 2 і 3 груп. Жорсткість тканини печінки в обстежених хворих коливалась від 2,3 до 8,8 кПа, а показник САР — від 108 до 349 дБ/м. У переважної більшості (96,1 %) пацієнтів фіброз був відсутнім; перший та другий ступінь фіброзу реєструвався лише в 3 пацієнтів (3,9 %) першої групи. За даними стеатометрії печінки середні показники коефіцієнта затухання ультразвуку в дітей 1 групи були вірогідно вищими порівняно з контрольною групою (p < 0,05). Чутливість методу зсувнохвильової еластографії щодо виявлення фіброзу печінки порівняно з транзієнтною еластографією становила 83,33 %, специфічність — 60,0 %, позитивна прогностична цінність — 15,15 %, негативна прогностична цінність — 97,67 %. При порівнянні методів стеатометрії та САР-функції транзієнтної еластографії в діагностиці стеатозу печінки в дітей 1 групи було виявлено збіг у 15 з 26 випадків, що відповідає діагностичній ефективності 57,7 %. Висновки. Таким чином, поєднання ультразвукових режимів оцінки структурних змін печінки із зсувнохвильовою еластографією та стеатометрією дає можливість оцінити стадію фіброзу й ступінь стеатозу в контексті мультипараметричного ультразвукового дослідження в дітей із дифузними змінами паренхіми печінки.

Актуальность. Ультразвуковое исследование является наиболее распространенным методом визуализации, используемым для диагностики стеатоза печени. Целью нашей работы является сравнение возможности диагностики стеатоза и фиброза печени с помощью стандартного ультразвукового исследования, сдвиговолновой эластографии со стеатометрией, транзиентной эластографии с использованием САР-функции. Материалы и методы. Обследовано 90 пациентов в возрасте от 5 до 17 лет, средний возраст пациентов составил (12,08 ± 2,71) года. Определение наличия и степени стеатоза печени проводилось с помощью аппарата FibroScan 502 Touch F60156 (Echosens, Франция) с исследованием САР. Всем детям проводилось ультразвуковое исследование паренхимы печени В-методом с одновременной сдвиговолновой эластографией и стеатометрией на аппарате Ultima PA («Радмир», Харьков). В зависимости от наличия стеатоза, который определялся по показателю САР, и избыточного веса и ожирения пациенты были разделены на 3 группы: 1 группу составили 45 пациентов со стеатозом печени и избыточным весом/ожирением (50,0 %), 2 группу — 35 пациентов с избыточным весом/ожирением без стеатоза (38,9 %), 3 группу (группа контроля) — 10 пациентов с нормальным весом без стеатоза (11,1 %). Результаты. Для пациентов со стеатозом было характерно повышение эхогенности печени (75,0 % пациентов). У детей 1 группы в 2,2 раза чаще наблюдалось изменение структуры паренхимы печени по сравнению с показателями 2 и 3 групп. Жесткость ткани печени у обследованных больных колебалась от 2,3 до 8,8 кПа, а показатель САР — от 108 до 349 дБ/м. У подавляющего большинства (96,1 %) пациентов фиброз отсутствовал; первая и вторая степень фиброза была зарегистрирована только у 3 пациентов (3,9 %) первой группы. По данным стеатометрии печени средние показатели коэффициента затухания ультразвука у детей 1 группы были достоверно более высокими по сравнению с контрольной группой (p < 0,05). Чувствительность метода сдвиговолновой эластографии относительно выявления фиброза печени по сравнению с транзиентной эластографией составила 83,33 %, специфичность — 60,0 %, положительная прогностическая ценность — 15,15 %, отрицательная прогностическая ценность — 97,67 %. При сравнении методов стеатометрии и САР-функции транзиентной эластографии в диагностике стеатоза печени у детей 1 группы было обнаружено совпадение в 15 из 26 случаев, что соответствует диагностической эффективности 57,7 %. Выводы. Таким образом, сочетание ультразвуковых режимов оценки структурных изменений печени со сдвиговолновой эластографией и стеатометрией дает возможность оценить стадию фиброза и степень стеатоза в контексте мультипараметричного ультразвукового исследования у детей с диффузными изменениями паренхимы печени.

Background. The purpose was to compare the possibilities of standard ultrasound, shear wave elastography with steatometry and transient elastography with CAP function for diagnosing liver steatosis and fibrosis. Materials and methods. The survey included 90 patients aged 5 to 17 years, with an average age of patients (12.08 ± 2.71) years. Determination of liver steatosis and its degree was carried out with FibroScan 520 Touch (Echosens, France) with CAP measurement. All children underwent an ultrasound examination of the liver parenchyma using B-method with simultaneous shear wave elastography and steatometry on Ultima PA (Radmir, Kharkiv). According to the CAP measurements and overweight/obesity parameters the patients were divided into 3 groups: 1st group consisted of 45 patients with liver steatosis and overweight and obesity (50.0 %), 2nd group — 35 patients with overweight and obesity without steatosis (38.9 %), 3rd group (control group) — 10 patients with normal weight without steatosis (11.1 %). Results. 75.0 % of patients experienced increased echogenicity of the liver. In children of the 1st group changes in liver parenchyma were observed 2.2 times more frequently than in the 2nd and 3rd groups. The liver stiffness in the examined patients varied from 2.3 to 8.8 kPa, and the CAP — from 108 to 349 dB/m. In the overwhelming majority (96.1 %) of patients, fibrosis was absent; the first and second degrees of fibrosis were found only in 3 patients (3.9 %) in the first group. According to steatometry of the liver, the average coefficient of ultrasound attenuation in children of the 1st group was significantly higher compared to the control group (p < 0.05). The shear wave elastography sensitivity in liver fibrosis detection versus transient elastography was 83.33 %, the specificity was 60.0 %, the positive predictive value was 15.15 %, the negative predictive value was 97.67 %. When comparing the methods of steatometry and CAP, the diagnosis of liver steatosis in children of the 1st group revealed coincidence in 15 of 26 cases, which corresponded to diagnostic efficiency of 57.7 %. Conclusions. Thus, the combination of ultrasound regimes for assessing structural changes in the liver with shear wave elastography and steatometry allows assessing the stage of fibrosis and the degree of steatosis in the context of multiparameter ultrasound examination in children with diffuse changes in the liver parenchyma.

Introduction

The liver biopsy is a gold standard for diagnosing liver steatosis in children and adults. However, in 2012, the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition proclaimed that liver biopsy should not be used as a screening procedure for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Indications for liver biopsy is still being discussed, and now there is no enough evidence to formulate a list of indications for this procedure in children with the primary diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), biopsy indication is stronger in the case of difficulties in carrying out differential diagnosis and in case of risk of progression to liver cirrhosis [1].

Non-invasive methods for diagnosing liver steatosis in children are important because they can be used to monitor the course of the disease for a long period [2]. Non-invasive ultrasound methods for diagnosing steatosis include standard ultrasound examination, sonographic quantification of a hepatorenal index, transient elastography, shear wave elastography.

Ultrasound. Ultrasound is the most common imaging method used to diagnose liver steatosis. Due to its wide availability, economic feasibility and simplicity of usage, ultrasound can be used as a liver pathology screening tool. A healthy liver parenchyma has a homogeneous echo texture and echogenicity similar to the echogenicity of the right kidney. In the case of liver steatosis, the presence of lipid drops within hepatocytes violates the propagation of the sound wave, causing the scattering and attenuation of ultrasound waves. The dispersion of ultrasound waves is manifested in the form of a more vivid visualization of liver parenchyma compared with the kidneys. The attenuation of ultrasound waves also causes loss of signal, which leads to darkening of vessels and bile ducts and blurred diaphragm [2]. Distal attenuation of ultrasound is usually typical for steatosis in the liver with lesions > 30 % of hepatocytes [1].

Classification of the degree of liver steatosis according to ultrasound data:

1. Absence of steatosis (echogenicity of the liver is similar to the kidney);

2. Slight degree of steatosis (diffusely increased echogenicity of the liver);

3. Moderate degree of steatosis (echogenicity of the liver reduces imaging of the walls of vessels and diaphragm);

4. Severe degree of steatosis (no imaging of the hepatic vessels and diaphragm) [3].

However, ultrasound study has some disadvantages: oper–ator and machine dependence, as well as the lack of objective quantitative analysis [1]. Ultrasound has low sensitivity for the differentiation between healthy liver and early steatosis and other pathological conditions such as fibrosis and/or inflammation, which may increase the echogenicity of the liver, sometimes can mimic liver steatosis. Therefore, an ultrasound evaluation of liver steatosis should be performed taking into account these constraints; the results should be carefully interpreted and this procedure should not be recommended as the only tool for diagnosing or monitoring NAFLD in children.

Hepatorenal index (HI). To calculate this indicator, the echogenicity of the liver and kidneys is evaluated in the study of the gray scale (value 0–255) using the built-in histogram. It is used with the average value of three repetitive measurements based on the ratio of the average echogenicity of the liver to the echogenicity of the kidney. A value below 1.0 is considered to be normal. The degree of steatosis is considered to be mild (HI 1.05–1.24), moderate (HI 1.25–1.64) or severe (HI ≥ 1.65). One of the disadvantages of –using HI is its variability and dependence on the operator and ultrasound apparatus [4].

Assessment of ultrasound attenuation. Quantitative estimation of the echo signal intensity can be used to objecti–vize the diagnosis of steatosis. There are methods for evaluating the parameters of the images in B-mode or analysis of the signal backscatter ultrasound waves [5]. Several studies have found an increase in liver attenuation coefficients and backscattering designed by ultrasound in patients compared with healthy persons [6]. However, most studies have been focused on differentiation of pathological and altered liver and did not estimate the severity of the NAFLD.

The attenuation coefficient represents the summation of ultrasound energy losses due to the echo reflection, scattering, and absorption. Studies showed that scattering has only a very small contribution to the attenuation coefficient in normal liver, but the dispersion of fat drops significantly affects the attenuation of US. In addition, studies of Kanayama et al. have shown that the number of lipid drops and their size in the liver tissues can greatly contribute to energy absorption in the spread of ultrasound [6].

Elastography. Ultrasound elastography is now increasing–ly used in the diagnosing diffuse liver disease. This –method provides the possibility of differentiation between simple steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis that has signs of inflammation and fibrosis [2]. There are several methods for ultrasound elastography, including transient elastography, shear wave elastography (SWE) and acoustic radiation force impulse elastography (ARFI).

Transient elastography. Transient elastography (Fibro–Scan 502 Touch) is a new non-invasive method for diagnosing fibrosis and most recently, due to the equipment of the apparatus with a new function, for the diagnosing steatosis as well [7]. Measuring the degree of steatosis is based on lipids ability to impact the spread of ultrasound. The calculation of the indicator characterizing steatosis degree — the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) — is due to the complicated process of ultrasound attenuation with its reverse propagation at an average frequency of 3.5 MHz [8]. CAP is an effective parameter for the determination of even low degree of steatosis. The study of V. de Lédinghen et al. showed that CAP significantly correlated with SteatoTest and the fat content of the liver, which was determined from the morphological study [9]. A 2014 meta-analysis by the Chinese scientists for the diagnostic accuracy of CAP to determine the degree of liver steatosis in various diseases has revealed that CAP has high sensitivity and specificity for determining the presence of liver steatosis, but is limited to precisely determining the degree of steatohepatitis that somewhat limits its wide application in clinical practice [10]. A recent study conducted in a small cohort of children who had a liver biopsy according to clinical indications identified a limit of 225 dB/m for predicting steatosis, 0.87 sensitivity, 0.83 specificity and AUROC 0.93 [11].

Therefore, transient elastography with FibroScan is a sufficiently sensitive method for non-invasive diagnosis of steatosis, which can be used for primary diagnosis and moni–toring of the effectiveness of treatment in children.

Shear wave elastography. The basis of SWE lies in the property of the ultrasound to excite the mechanical shear wave transverse to its direction. The velocity of propagation of these waves depends on tissue rigidity or viscoelastic properties [12]. The real-time SWE has some advantages over TE. First, this function is integrated in the usual ultrasound apparatus, and therefore, can use the real-time image in the B-mode to assess morphological changes or to detect of focal lesions of the liver. Advantage of SWE, as well as ARFI, is to provide a quantitative map of liver tissue stiffness in real time. The spatial heterogeneity of the liver stiffness can be visualized, and the area of interest used for measurement can be corrected. The area of interest for liver stiffness measurements can be adjusted in size and location to avoid such artifacts as those occurring near large pulsating vessels [13].

The purpose of our work is to compare the possibilities of diagnosing steatosis and liver fibrosis by using standard ultrasound study, SWE with steatometry and transient elastography using the CAP function.

Materials and methods

The survey included 90 patients aged 5 to 17 years: boys — 54 (60 %), girls — 36 (40 %). The average age of patients was (12.08 ± 2.71) years. The assessment of BMI was carried out according to the WHO recommendations (gender and age specific) [14].

Determination of the presence and degree of liver steatosis was carried out with FibroScan 502 Touch (Echosens, France) with CAP measurement (Table 1) [15]. An M-sensor with an ultrasonic frequency of 3.5 MHz was used. Also we determined the changes in elasticity or stiffness of the liver (LSM) which indicates the development of fibrosis, and the CAP, which corresponds to steatosis degree. The liver stiffness was evaluated in kilopascals (kPa), viscosity or steatosis — in decibels per meter (dB/m).

The obtained parameters of liver stiffness were evaluated as follows: elastometric parameters up to 5.9 kPa corresponded to the stage of fibrosis F0; 6–7.0 kPa corresponded to the stage of fibrosis F1, from 7.1 to 8.7 kPa — stage F2, over 8.7 kPa — F3 on Metavir score [16].

Also ultrasound examination of the liver parenchyma by the B-method with simultaneous shear wave elastography and steatometry on the Ultima Expert (Radmir, Kharkiv) with a cone-shaped sensor at frequencies of 2–5 MHz at a depth of 10–50 mm from the capsule was performed. The number of successful measurements should have been at least 3. Then, from the indicated measurements, the median characterizing the liver stiffness in kilopascals as well as the average coefficient of ultrasound attenuation (UAC) (dB/m) were determined.

Depending on steatosis presence, determined on the basis of CAP, and presence of overweight and obesity the patients were divided into 3 groups: the 1st group consisted of 45 patients with liver steatosis and overweight/obesity (50.0 %), the 2nd group included 35 patients with excessive weight and obesity without steatosis (38.9 %), the 3rd group (control group) consisted of 10 patients with normal weight without steatosis (11.1 %). The exclusion criteria were the presence of secondary causes of steatosis (viral, autoimmune hepatitis, storage diseases) and concomitant chronic or acute diseases.

Results

Standard ultrasound data

Average values of the size of the liver and gallbladder are given in Table 2.

The largest liver size was observed in the 1st group of patients (p < 0.01). A detailed analysis of these parameters, depending on the growth of a child, also showed that almost all (88.9 %) of the children in the 1st group experienced an increased size of the liver due to all the lobes.

The echogenicity of the liver was increased in 3/4 of the patients with overweight/obesity (73.7 % in the 1st group patients and 61.1 % in the 2nd group). For the analysis of structural changes in the liver, the following characteristics of the parenchyma were assessed: granularity, echogenicity, and distal attenuation of ultrasound. Specific for patients with steatosis was granular structure of the liver, which was observed in 36 patients (80.0 %).

In children of the 1st group the changed structure of the liver parenchyma was detected 2.2 times more frequently than in the 2nd and 3rd groups (37.1 and 30.0 %, respectively) (Fig. 1).

In the majority of the 1st group patients elevated and uneven liver echogenicity was observed (75.6 and 71.1 %, respectively). Distal ultrasound attenuation was detected 2 times more frequently in this group than in the 2nd group children.

It should be noted that in children with steatosis imaging of the hepatic veins significantly worsened: in the 1st group children hepatic veins imaging deterioration was observed 2 times more often than in the 2nd group.

Data of transient elastography

The parameters of liver parenchyma stiffness and CAP in children with obesity and overweight according to transient elastography data are given in Table 3.

The liver stiffness in the examined patients varied from 2.3 to 8.8 kPa, and the CAP index — from 108 to 349 dB/m. In the overwhelming majority (96.1 %) of patients, fibrosis was absent; the first and second degree of fibrosis was registered only in 3 patients (3.9 %) in the 1st group.

As can be seen from the data in Table 3, liver stiffness rates, although not exceeding the norm, were significantly increased in children with steatosis.

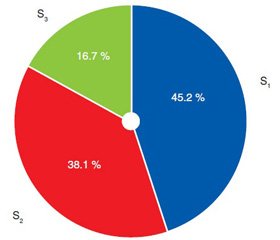

Among the patients with steatosis 45.2 % had the first stage (up to 33 % of hepatocytes contained fat) and 16.7 % had the third stage of fatty degeneration — almost all hepatocytes had fat inclusion (Fig. 2).

Data of shear wave elastography and steatometry

Taking into account liver structural changes, SWE of the liver was performed to evaluate the stiffness of the parenchyma in the examined children. The average values of liver stiffness are given in Table 4.

When comparing liver parenchyma stiffness in groups, a significant increase in this parameter in obese children was established in comparison with the control group. In children with steatosis, higher stiffness rates (although not exceeding normal) were observed compared to children with simple obesity without fatty liver (p < 0.05).

According to liver steatometry findings, the average coefficient of ultrasound attenuation in the 1st group children was significantly higher compared to the control group (Table 5).

Comparison of SWE and TE data

When comparing SWE with TE (FibroScan) according to contingency table (Table 6) a match in fibrosis detection in 47 of the 76 surveyed (presence of fibrosis in 5 children out of 6 children and lack in 42 patients out of 70) was found, which corresponds to 61.8% diagnostic efficiency.

SWE sensitivity for liver fibrosis detection compared with transient elastography was 83.33 %, specificity — 60.0 %, positive predictive value — 15.15 %, negative predictive value — 97.67 % (Table 7).

When comparing the steatometry findings and CAP in the diagnosis of liver steatosis in children the coincidence was found in 15 out of 26 cases (steatosis in 14 out of 23 and steatosis absence in 1 patient out of 3), which corresponds to 57.7% diagnostic efficacy (Table 8).

The steatometry sensitivity for liver steatosis detection was 60.87 %, the specificity was 33.33 %, the positive predictive value was 87.50 %, and the negative predictive value was 10.00 % (Table 9).

Discussion

Thus, the sonographic signs of fatty liver in obese/overweight children were a significant elevation in the liver size, which was accompanied by increasing the liver parenchyma echogenicity in 75.6 % (p < 0.05) of cases, changes in the liver granularity (80.0 %), by increasing the length of the spleen. The liver size increasing and liver parenchyma structure alteration (changes in contours and granularity, increased echogenicity) were also found more frequently in patients with fatty liver.

The liver steatosis according to TE was detected in 22 children (44.4 %) with no evidence of steatosis in standard ultrasound study. These data indicate that CAP can diagnose early stages of liver steatosis.

It should be noted that the use of TE has some limitations. Thus, the presence of ascites excludes the possibi–lity to carry out transient elastography, i.e. elastic waves are not able to pass through the liquid; the presence of morbid obesity with BMI > 30 kg/m2 requires the use of XL sensor, the use of M sensor in such patients is associated with high variability of values and the impossibility of obtaining an average CAP. LSM is also limited by a number of factors: the presence of acute hepatitis is accompanied by changes in liver parenchyma, which can lead to an increase in LSM levels; the presence of chronic hepatitis with ALT level > 5 UNL is accompanied by a re-assessment of fibrosis stage; the presence of extra-hepatic cholestasis is also accompanied by an increase in liver stiffness, and the presence of narrow intercostal spaces may reduce the possibility of the method [17].

Taking into account these limitations, an algorithm for interpreting the data of transient elastography for the diagnosing liver fibrosis in adult patients was offered (by Chan in the Wong modification) (Fig. 3) [18].

However, we want to focus attention on the fact that transient elastography is one of the most valid non-invasive diagnostic methods for liver steatosis and fibrosis detection, characterized by high reproducibility, high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. The unconditional benefits are painlessness, short duration of the examination, which makes TE almost an ideal method for liver pathology screening in the general population.

In our study children with fatty liver showed higher LSM values compared with children without steatosis on 0.7 kPa. Although this profile was not clinically relevant, since in most patients the liver stiffness remained within the normal range, we would like to emphasize that signs of liver fibrosis were observed in a small percentage of children with liver steatosis and any child without it. This conclusion confirms that liver steatosis is not always a benign condition; therefore, measures should be taken to evaluate the disease at an early stage.

It should be noted that according to Tokuhara et al. study, TE was performed in 139 healthy children aged 1 to 18 years, the setting of LSM was proportional to age (which is probably due to physiological changes in the liver connective tissue in children and adolescents), while the CAP value did not distinguish in children of different age groups, which testifies to the absence of age-related –changes in the lipids distribution in the parenchyma of healthy liver [19].

Concerning the SWE, studies conducted in adults have shown that early stages of fibrosis are difficult to detect by elastographic imaging: measurements obtained in early fibrosis are similar to those obtained in healthy patients [20]. The literature data on the influence of steatosis on the elastography values revealed contradictory results. Marginean et al. [21] found that the liver stiffness values according to ARFI in children with steatohepatitis were significantly higher than in the control group, suggesting that liver steatosis leads to increase in the liver parenchyma stiffness. Instead, Wong et al. [22] report that liver steatosis does not impact the degree of liver fibrosis.

In our study, the liver stiffness was higher in children with NAFLD. It should be noted that high elastographic values can be mistakenly considered as severe liver fibrosis, but the influence of steatosis on the stiffness cannot be ruled out.

According to Garkovich et al. [23], providing SWE in 68 children with steatohepatitis a strong correlation between liver stiffness and morphological stages of liver steatosis was established. However, there was no association between the liver stiffness parameters and the morphological features of steatosis and necro-inflammation. Relevant data demonstrate the importance of SWE combination with liver steatometry.

Our research demonstrated satisfactory diagnostic efficacy of SWE and steatometry in comparison with transient elastography and CAP function when diagnosing liver fibrosis and steatosis.

Conclusions

Thus, the combination of ultrasound regimes with shear wave elastography and steatometry in the context of multiparameter ultrasound examination for assessing liver structural changes allows evaluating the stage of fibrosis and the degree of steatosis in children with diffuse changes in liver parenchyma.

So, transient elastography allows accurately assessing the degree of fat accumulation in the liver parenchyma at the same time as determining the degree of fibrosis. However, a standard ultrasound study maintains the position as it can exclude hepatic masses, cysts, or gallbladder pathology but according to NASPGHAN guideline (2017) a normal hepatic ultrasound cannot exclude the presence of NAFLD and therefore is not useful for the diagnosis or follow-up [24].

Conflicts of interests. Authors declare no conflicts of interests that might be construed to influence the results or interpretation of their manuscript.

Список литературы

1. Vajro P. Diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: position paper of the ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee / P. Vajro, S. Lenta, P. Socha et al. // Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. — 2012. — Vol. 54, № 5. — P. 700-713.

2. Di Martino M. Imaging Features of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents / Di Martino M., Koryukova K., Bezzi M. et al. // Children. — 2017. — Vol. 4(8). — P. 73. doi: org/10.3390/children4080073.

3. Awai H.I. An evidence and recommendations for imaging liver fat in children, based on systematic review / H.I. Awai, K.P. Newton, C.B. Sirlin et al. // Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. — 2014. — Vol. 12. — P. 765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.050.

4. Isaksen V.T. Hepatic steatosis, detected by hepatorenal index in ultrasonography, as a predictor of insulin resistance in obese subjects / V.T. Isaksen, M.A. Larsen, R. Goll et al. // BMC Obesity. — 2016. — Vol. 3. — P. 39. doi: org/10.1186/s40608-016-0118-0.

5. Liao Y.Y. Multifeature analysis of an ultrasound quantitative diagnostic index for classifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease / Y.Y. Liao, K.C. Yang, M.J. Lee et al. // Scientific reports. — 2016. — Vol. 6. — P. 35083.

6. Kanayama Y. Real-time ultrasound attenuation imaging of diffuse fatty liver disease / Y. Kanayama, N. Kamiyama, K. Maruyama et al. // Ultrasound Med. Biol. — Vol. 39. — 2013. — P. 692-705.

7. Goldschmidt I. Application and limitations of transient liver elastography in children / I. Goldschmidt, C. Streckenbach, C. Din–gemann et al. // Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. — 2013. — Vol. 57 (1). — P. 109-113.

8. Sasso M. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a novel VCTE™ guided ultrasonic attenuation measurement for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis: preliminary study and validation in a cohort of patients with chronic liver disease from various causes / M. Sasso, M. Beaugrand, De Ledinghen et al. // Ultrasound in medicine and Biology. — 2010. — Vol. 36 (11). — P. 1825-1835.

9. De Ledinghen V. Non-invasive diagnosis of liver steatosis –using controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and transient elasto–graphy / V. De Ledinghen, J. Vergniol, W. Merrouche et al. // Liver Int. — 2012. — Vol. 32 (6). — Р. 911-918.

10. Shi K.Q. Controlled attenuation parameter for the detection of steatosis severity in chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy / K.Q. Shi, J.Z. Tang, X.L. Zhu et al. // J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. — 2014. — Vol. 29 (6). — P. 1149-1158.

11. Desai N.K. Comparison of controlled attenuation para–meter and liver biopsy to assess hepatic steatosis in pediatric patients / N.K. Desai, S. Harney, R. Raza et al. // J. Pediatr. — 2016. — Vol. 173. — P. 160-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.021.

12. Динник О.Б. Жорсткість печінки за даними зсувно–хвильової еластографії у хворих на цукровий діабет типу 2 з неалкогольною жировою хворобою печінки залежно від активності процесу НАЖХП / О.Б. Динник, Г.П. Михальчиши, Н.М. Кобиляк та ін. // Гастроентерологiя. — 2014. — Т. 53, № 3.

13. Tutar O. Shear wave elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in children / O. Tutar, Ö. F. Beser, I. Adaletli // Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. — 2014. — Vol. 58, № 6. — P. 750-755.

14. World Health Organization: Growth reference 5–19 years. BMI-for-age (5–19 years). doi: who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en/

15. Masaki K. Utility of controlled attenuation parameter measurement for assessing liver steatosis in Japanese patients with chronic liver disease / K. Masaki, S. Takaki, H. Hyogo et al. // Hepatol. Res. — 2013. — Vol. 43 (11). — P. 1182-1189.

16. Degos F. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study) / F. Degos, P. Perez, B. Roche et al. // J. Hepatol. — 2010. — Vol. 53. — P. 1013-1021.

17. Mikolasevic I. Transient elastography (FibroScan®) with controlled attenuation parameter in the assessment of liver steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease — Where do we stand? / I. Mikolasevic, L. Orlic, N. Franjic // World Journal of Gastroenterology. — 2016. — Vol. 22 (32). — P. 7236-7251. doi: org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i32.7236.

18. Chan H.Y. Alanine aminotransferase-based algorithms of liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography (Fibroscan) for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B / H.Y. Chan, G.H. Wong, P.L. Choi et al. // Journal of viral hepatitis. — 2009. — Vol. 16 (1). — P. 36-44.

19. Tokuhara D. Transient Elastography-Based Liver Stiffness Age-Dependently Increases in Children / D. Tokuhara, Y. Cho, H. Shintaku et al. // PloS one. — 2016. — Vol. 11 (11). — P. e0166683.

20. Yoneda M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: US based acoustic radiation force impulse elastography / M. Yoneda, K. Suzuki, S. Kato et al. // Radiology. — 2010. — Vol. 256. — P. 640-647.

21. Marginean C.O. Elastographic assessment of liver fibrosisin children: a prospective single center experience / C.O. Marginean, C. Marginean // Eur. J. Radiol. — 2012. — Vol. 81. — P. 870-4.

22. Wong V.W. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liverdisease / V.W. Wong, J. Vergniol, G.L. Wong et al. // Hepatology. — 2010. — Vol. 51. — P. 454-62.

23. Garcovich M. Liver stiffness in pediatric patients with fatty liver disease: diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility of shear-wave elastography / M. Garcovich, S. Veraldi, E. Di Stasio et al. // Radio–logy. — 2016. — Vol. 283 (3). — P. 820-827.

24. Vos M.B. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) / M.B. Vos, S.H. Abrams, S.E. Barlow et al. // Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. — 2017. — Vol. 64 (2). — P. 319-334. doi: org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001482.

/41-1.jpg)

/42-1.jpg)

/43-1.jpg)

/44-1.jpg)